History

It's important to note that racism within fashion, luxury, and retail is not a modern dilemma, but instead stems from centuries of systematic oppression.

Magazines and Models

We begin in 1892, the year that Vogue magazine was founded. From then to 2012, less than one percent of Vogue covers featured minorities of any kind. From 2012 to now, the number of covers with minorities has increased by 6 covers.

Even so, once magazines started to picture minority models in their magazines, they did it with a racist undertone. Alec Wek, a South Sudanese British supermodel, describes in her 2007 book "Alek: From Sudanese Refugee to International Supermodel", images she took for Lavazza coffee where she sits in a giant coffee mug as a stand-in for actual espresso.

"I can't help but compare them to all the images of black people that have been used in marketing over the decades. There was the big-lipped jungle-dweller on the blackamoor ceramic mugs sold in the Forties; the golliwog badges given away with jam; Little Black Sambo, who decorated the walls of an American restaurant chain in the 1960s; and Uncle Ben, whose apparently benign image still sells rice," she said.

Racism within the industry is even seen within management. Elite Model Management was caught on tape using racial slurs and stating that Africa would be a much better place if it were full of white people. Executives within the company even said that Milan would never accept "a black or Oriental" model walking the runway.

C-Suite and Leadership

Most of the discourse of racism in FL&R is centered around models and magazines. Of course, models have historically experienced many forms of discrimination, but, the history of racism within FL&R is much deeper and thus the discourse must follow suit. One aspect that is commonly overlooked is the topic of management and its influence throughout the fashion industry. This includes those from the entry-level to the boardroom, where the power is concentrated.

A January 7th report, from the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA), called out the lack of diversity and inclusion within the industry. Research has shown that white men are overly represented in c-suite positions (53%) and sit on boards as fashion companies (73%). On the other hand, employees of color only make up 16% of c-suite positions and 15% of board positions. This lack of diversity has negatively rippled throughout the industry by creating an unwelcoming environment. Over two-thirds of Black employees have felt been the only Black person in the room, resulting in increased pressure to perform and succeed.

These issues start at places where BIPOC young creatives are not given the same opportunities as their white male counterparts. At the top fashion schools in the United States and the United Kingdom, over 70% of students are white. Black students make up less than 10%, Asian students less than 8%, and the remaining labeled as Mixed or Other. Moreover, BIPOC professors teaching within the classrooms are few. Only six per cent of full-time faculty in US universities were Black in autumn 2018, compared to 73 percent of white staff.

History of Outsourcing

If you were to look at the clothes from big fast fashion brands, such as H&M, Zara, or Forever 21 to name a few, you would see a "Made in China" tag on the collar. This tag comes from the result of outsourcing to produce their products. Outsourcing is when companies hire an outside party to create their products, usually in countries where labor is considered cheap. Outsourcing is a process adopted by many companies starting in the 1970's and then becoming a norm starting in the 1980's.

As of today, less than 3% of US clothing is made in the country and a staggering 97% being outsourced from countries such as Bangladesh, China, and India. However, the unethical treatment of garment workers at these factories are no where near a respectable work environment. Less than 2% of all garment workers are payed a living wage and similar numbers are working in conditions that are safe. Part of the problem is that conversations about garment worker treatment is silenced and hidden from the media. One of the first worldwide news coverage of garment workers was from the devastating 2013 Dhaka garment factory collapse. Even though 1,134 lives were taken, atrocities like this are uncommon but not rare in the Rana Plaza area. Even so, large companies such as H&M, Forever 21, and Zara, are silent on this issue even though they themselves perpetrators.

Today, companies are manufacturing clothes at an alarming rate and consumers are buying at a similar one. The world now consumes about 80 billion new pieces of clothing every year, with millions more being thrown into a landfill, never to see a closet or dresser. The issue of unethical outsourcing and its impact on communities has only been exacerbated in the last few years due to the increased demand of fast fashion. A more modern outline of this issue can be seen in the Labor & Supply Chains section of this page.

Fashion and Racially Charged Violence

Fashion, in context with history, opens a lens. In 1943, Zoot suits, in simple terms a high-waisted, wide-legged trouser paired with a long-coat, started to become popular among young men in African American, Mexican American, and other minority communities. In the context of World War 2 and the rationing of fabrics to make soldiers' uniforms, these suits were seen as "unpatriotic" by white Americans. Racial tensions increased in the city, with minority individuals being unjustifiably accused of each crime. With that, biased Los Angeles media painted "Zoot suit wearers" as violent criminals, only adding fuel to the fire. It was later in that summer of '43 when US servicemen took to the streets and began attacking Latinos and stripping them of their suits, leaving them bloodied and half-naked on the sidewalk. The Zoot suit became a target in what was a racist attack on minority communities.

Visibility, Aesthetics, & Socio-Cultural Issues

Fashion intersects with various issues that are commonly not talked about. However, these issues are important to highlight to start those conversation and make them more common. In this section, we will highlight a few issues that are commonly over looked as a way to start the conversation around them, as well as provide resources throughout on where to continue learning.

Cultural Appropriation and Exploitation

As stated before, racism is embedded in different levels and areas within FL&R. Most recently, social media has brought to light the disregard of cultural appropriation that brands have put into their designs and actions. A notable example in luxury fashion is Gucci's 2019 offensive blackface sweater that went for $890. NPR reported on the controversies and Gucci's statement, highlighting the history of blackface and its overwhelming show within fashion. Cultural appropriation also emerges on the runway, most notably Comme de Garçons 2020 Paris Fashion week runway show. Comme de Garçons had white models wear cornrow wigs, a notable Black culture related hairstyle. While the Japanese brand came out and said that they had "no intention to disrespect or hurt anyone", it goes to show that lack of awareness and education is at the heart of many cultural appropriation instances. Diet Prada further covered this story, stating that "the avant-garde Japanese label seemed to have taken a step back with their men's show, this time putting white models in cornrow wigs". These are only two examples of many that cultural appropriation within fashion has been noted.

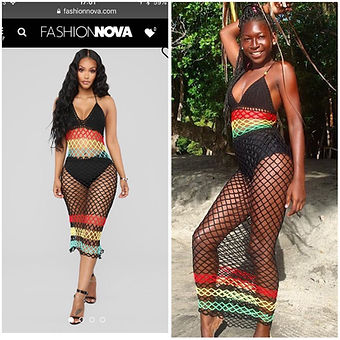

The fashion industry further harms BIPOC creatives by stealing their designs. In 2019, designer Luci Wilden discovered that Fashion Nova stole their crochet design. Wilden stated “…not only are they stealing my design, but they’re using it to exploit people and profit from it.”. This is only one instance of many where the fashion industry has not given credit where credit is due to BIPOC designers.

Socio-Cultural Issues

Fashion, luxury, & retail has a modern problem of being non-inclusive towards varying sizes. Today, unrealistic Euro-centric beauty standards say that all women must fit a size 0-4. This unrealistic standard feeds the vividly present lack of self-esteem in many women and men. According to Park Nicollet Melrose Center, nearly 70% of healthy people desire to be thinner and 80% "do not like how they look". With the average American women's size being a size 16-18, and men's average waist size being 40, and with most brands topping their clothes at a size 12-14, why are brands not doing more to create clothes that fit consumers? It is this perpetuation of fatphobia from the fashion industry that make unrealistic and harmful body shapes the "ideal". Moreover, certain clothing trends and styles are seen as a revolutionary and acceptable on a thin white person versus a curvier person. For example, baggy and oversized clothing is deemed as a "a feminist revolt against tighter clothes" on the body of a white thin women versus seen as lazy and frumpy on the body of a curvier person. This exclusivity within fashion is nothing new, and is one of the largest reasons on why the fashion industry has created a traumatizing and harmful environment for many.

Some retailers and platforms have begun to put in the right work needed to change the norm within fashion. A notable example is e-tailer 11 Honoré, a luxury online clothing retailer that focuses on clothing from sizes 10 to 20. Check below at the Platforms & Brands section to find a few more.

"The fashion industry perpetuates unrealistic and harmful body shapes as the "ideal"

-(Lowest Wage, 2021)-

Size Inclusivity

Combatting the Binary

In the fashion industry, consumers are forced to choose between the gender binary when shopping for clothing, even if they do not particularly identify as either-or. This binary in clothing is extremely limiting, especially for young adults who are exploring their own gender and sexual identities. Moreover, the representation of androgynous and gender non-conforming models are limited. Non-binary models have come forward and stated that they feel as if they are being "forced to conceal their identities” in order to succeed in the fashion industry. The fact is, the fashion industry is still following outdated gender norms that serve no one. However, newer brands have started to adopt gender-neutral apparel sections into their clothing. Some of the leading brands include The Phluid Project, Les Girls Les Boys, Tomboy X, and Wildfang.

Labor & Supply Chain Issues

Buying clothes is one thing, but knowing where they came from is another. The fashion industry has silenced and hidden the truth about where fast-fashion clothing is made and how harmful the garment lifecycle is for millions around the world.

"In the garment industry, 85% of the workers are women"

-(UAB 2018)-

The fashion industry has evolved to become a fast-producing industry for brands that mainly focus on staying up with the latest trends and each other. However, that has opened many doors for exploitation and unethical practices that companies use to keep up with these trends and with each other. Prior to the 1960s, 90% of garments were created in the United States; now, it's reduced to less than 3%. The increased outsourcing of labor has a positive correlation with the unethical treatment of garment workers in the industry. As of 2020, garment workers have been paid merely 2-6 cents per garment, work 60-70 hour work weeks, and earn only $300 a week. Moreover, garment workers are forced to work in unsafe conditions and are given little to no break throughout the day. The true cost of fashion can be better described in the media found below.

Media Gallery

Inside look at Fast Fashion Impacts

Environmental & Economic Issues

Environmental racism is the disproportionate impact of hazardous environmental changes in communities of color. Worldwide, communities of color have been impacted by the fashion industry at every step of the garment lifecycle. This has been caused by western nations exploiting workers worldwide.

Environmental Racism

The fashion industry is one of the leading environmental hazards today. The garment industry is estimated to produce over 1.7 billion tonnes of CO2 emission each year as well as being 20% of all water industrial pollution. Moreover, over half a million tons of micro-plastics are dumped into oceans each year by the overuse of cheap polyester clothes. On top of that, most of this pollution occurs in low-income communities of color. Moreover, it's at every stage of the garment lifecycle where communities of color are affected. At the productions stage, garment workers are constantly exposed to hazardous fumes, which lead to serious health problems. During the dying process, run-off water is dumped into the surrounding waters of the communities. This water is full of contaminants and hazardous chemical dyes that make the water non drinkable. In China, more than 70% of the waters throughout the country are contaminated by over 2.5 billion tons of runoff water due to the fashion & textile industry.

Economic Racism

Fashion brands have evolved from producing two collections a year to five and with that, quantity has surpassed quality. Yet, our consumption of fast fashion has only been increasing, with garment purchases increasing by over 60% since the year 2000. While over 80 million garments are produced each year, more than 80% of those eventually end up in incinerators at landfills. This overconsumption of fast fashion has become a worldwide health hazard that is easily overlooked.

"More than 70 million people are employed within the fashion and retail industry"

-(Fashion United, 2020)-

Tied with this issue is the exploitation of workers throughout the garment lifecycle. People of color are doing the work while white CEO's and c-suite members are reaping the benefits from the comfort of the business table. It's known that 26 billionaires own around half of the world's wealth. Of these 26 billionaires, 9 of them are related to the fashion and retail industry.

Inequality within the fashion industry has been hidden by the supposed democratic idea that fast fashion is affordable for everyone. Yet, the reality is that fast-fashion has been built from a globalized and systemic racism that is only getting worse by the minute. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to light the reality of fast-fashion and its harmful impact on communities, as well as the disparity between western nations and the rest of the world in regards to the fashion industry. Since the pandemic started, the US and the UK has rejected over $16 billion worth of exported goods and products, according to The Center for Global Worker's Rights. This huge financial loss caused already suffering workers in countries such as Cambodia, Myanmar, and Bangladesh to lose jobs and fall into deeper poverty. Western nations are able to exploit this cheap labor due to little regulations brought upon these factories. They are able to order in bulk from garment factories and don’t have to honor contracts until the items are made and transported: including being able to drop-out at the last minute. This economic imbalance is what allows garment factories to continue paying their workers a non-livable wage, force workers to work in dangerous environments, and leaves the poorest out of work while prioritizing the pockets of rich CEO's.

To learn more about labor and supply chains issues, look at this section on this page. Moreover, refer to Good On You quick facts about fast fashion as well as Diet Prada's real, truthful, and descriptive reporting on various issues within fashion.

Anti-Racist Platforms and Brands

Many people have started to break into the fashion industry through various initiatives from the management to the creative level. The following initiatives were all created with a similar goal in mind: to boost creatives and leaders within the fashion industry who have been historically silenced.

The 15% Pledge

<span style="letter-spacing:0.03em;" class="wixui-